Premier Writing showcases poetry, essays, and short fiction by new and emerging Irish writers. This week’s short story is by Steve Wade from Dublin.

Short Story

Don’t Let Go

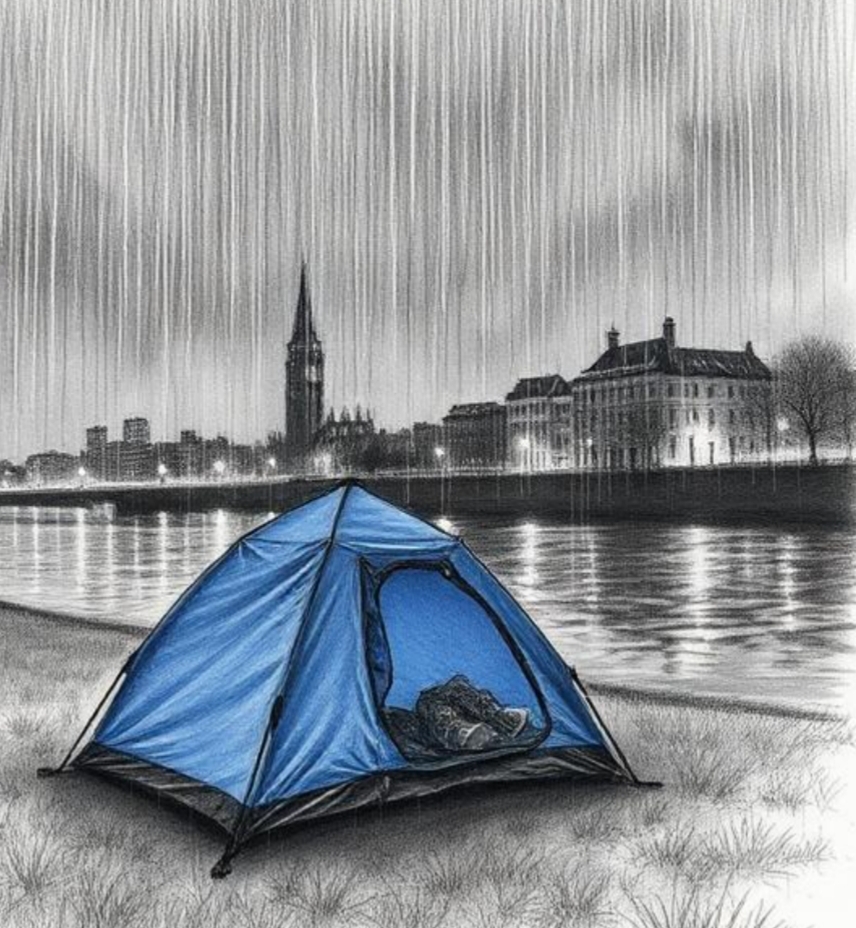

THE HEAVY RAIN pooled in places on the roof of their tent, then seeped through the nylon. To give her shelter, Bennett mantled Yusra’s prostrate body as best he could, without putting too much weight upon her chest. This he did by staying on his knees and stretching sideways across her torso, his body supported by his elbows. The leaking water dripped onto his arched back, soaking into the polyester of the open sleeping bag he wore drapedabout him like a cloak.

They had met while he was backpacking around Europe and the Middle East. To support himself, Bennett did whatever work came his way – harvesting, cleaning, kibbutz volunteer, hostel work and other low-end employment. Yusra was a receptionist in a hostel when he was given the position of caretaker.

Aware of and respectful of the custom which forbade casual interaction between men and women in her country, his role doing maintenance and repairs allowed him to talk to her as a colleague. He made her laugh with his silly stories, while her positive energy and slightly crooked smile caused the air around them to crackle.

They arranged to meet in secret. On their days off they travelled to other towns and met up in cafes. Even then, he put on simple disguises – just in case. He wore a false beard. Or used a facemask and baseball cap. Sometimes, if there were too many people about, they sat at nearby tables, content to communicate by text message and surreptitious glances and gestures. These clandestine meetings added to the excitement of their perilous liaison.

Every waking and sleeping moment had led to this kiss.

Despite the societal restrictions under which they existed, Yusra often surprised him. Like that evening when he hailed a taxi to take her home. Before she got into the car, she allowed him to guide her into the shadows away from the old taxi driver’s view in the wingmirror, where he kissed her. Their first kiss. Her soft lips crushing against his sent electricity shooting through him. And he understood there and then that everything he had ever done, every footfall he had ever made, every gesture, every waking and sleeping moment had led to this kiss. She, Yusra, and he, were meant to be. Their story was written.

Not long after that kiss, they attempted to book into a hotel room. But the male receptionist asked the manager on duty to intervene.

“It’s not a good idea,” the manager said in good English. “For the hotel and for your safety too.”

“Safety from what?”

The manager ignored his question and advised him that instead they should sit in the foyer, where they could talk and share a coffee. Yusra kept her head down but increased the pressure of her hand on his arm. He got it and complied with the hotel manager’s suggestion.

“The police,” she confirmed when they sat down. “They could call the police. I know my people.”

“Don’t worry. I understand.”

They sat for a while in that hotel foyer, before leaving separately in different taxis. She left first, while he used the toilet, then he asked the receptionist to call another taxi.

For two years they continued in this manner. That changed when tectonic plates shifted beneath the earth. There followed a crash of seismic waves. In seconds, hundreds of thousands of buildings collapsed, ending the lives of countless thousands. Bennett and Yusra were among the lucky ones to survive.

With the smell of burning cables, fuel, and the sickly-sweet stench of death all about them, she agreed to flee the life of government supplied tents to travel to his country. And here they now were sleeping in an even flimsier tent on the streets of his city. He could imagine how she felt during moments like this. She had abandoned her family, deserted her country to be with him. For what?

Their dream of getting a small place to live had been put on hold. There were visa issues for Yusra. Her time as a visitor had run out. They lived in constant fear that the authorities who sometimes questioned them on the streets, who asked them for official documents, would initiate her deportation. And, for Bennett, because he had no fixed abode, no employer would entertain the possibility of giving him a job.

Determined to keep Yusra safe and prevent her from being deported back to her own country and all the horror that went with it, Bennett got in touch with a childhood friend who ran a guesthouse in the West. Bennett had tracked him down some years back, but they hadn’t got around to meeting up before he left the country to seek work and adventure abroad. Without revealing Yusra’s true status as a now illegal immigrant, Bennett told his friend that he was finally able to take up the invitation to visit him. He and his new wife. If, of course, the invitation still stood.

Cormac, his childhood friend, reextended the invitation, saying they could stay as long as they liked. And this he meant, Bennett knew. Seventeen rooms he had in his guesthouse, and these were only in use during peak times. So, there’d be no problem with accommodation. And no hurry was there with payment of any sort. As soon as they got some work, they could contribute to the household. And even then, he wasn’t too pushed.

Bennett’s embarrassed response at his friend’s hospitality was to quip that he was trying to kill him with kindness. But when he closed the phone call, the gratitude he felt made him weep like some ancient widow who had outlived her only child.

What would his mother and father think if they were still alive and privy to his contemplations?

Despite his friend’s magnanimous offer, there was the burning reality of finance. The cost of the train fare alone would be over a hundred euro. This was a greater amount than he had had in his pocket since they had returned to his country nearly a year ago.

Money. They needed money. To survive till now, Bennett had mostly kept it legal. Not by choice, but as a necessity. Crime, petty or otherwise, was a surefire way of drawing unwanted attention on Yusra if he was caught. And everyone got caught at some stage. This he had direct experience of while doing parttime work in the security area back in his college days.

A plan. He spent the rest of the freezing, rain-soaked night mulling over ways to gather funds for the cost of two one-way tickets to the West. Tapping was one of them. The term used by the street people he sometimes talked to when they regarded him as one of their own. But, no, he wasn’t yet ready to sit on the pavement, a Styrofoam cup in his hand. What would his mother and father think if they were still alive and privy to his contemplations?

Unsummoned scenes from his childhood flickered about in his head. His mam’s smiling face and China-blue eyes the day he won First Prize in the Texaco Art Competition. The trips in the Ford Mondeo to the West, where every year they stayed in the white cottage they rented from Cormac’s parents. That time he and his dad went fishing in the currach and the weather turned. Without warning, the kingfisher-blue sky vanished, replaced by an ominous charcoal-grey. The waters whipped up, slapping him in the face with salty spray, before their boat was tipped over as though it were a child’s toy.

Yusra moved in her sleep next to him. Bennet clamped his hand over his mouth and brushed a lock of sodden hair from across her brow. He swallowed, his throat contracting.

I’ve got you, son, his father’s voice spoke in his head. It’s okay. Keep your head above the water. That’s it. Hang onto me. Don’t Let Go.

And hang on he did. His father’s strong arm wrapped about him like a ring of steel. With his other hand, his father clung to the upturned boat. Bennett could still feel the icy waters penetrating him to the marrow, as the sea rocked and spun the currach about in its efforts to claim them. The mouthfuls of water he inadvertently swallowed burned his insides like liquid fire.

The orange of the rescue boat coming through the hellish waters that day returned like the hazy image it had been when he and his father realised it wasn’t some desperate, near-death mirage. Accompanying the expanding boat while it drew nearer was the chop-chop thumping of the helicopter overhead.

Too rough for the rescue boat to manoeuvre close enough without risk of further endangerment, the boatmen and the helicopter pilot and crew worked together to guide and winch Bennett and his father to safety.

…a woman whose heavy-lidded eyes were the eyes of someone ready to accept defeat.

Morning arrived and with it a warming sun. Bennett brought Yusra to the toilets in the shopping centre, where they dried up and tidied themselves. With a takeaway coffee and a bun from a café for breakfast, he brought her to the relative warmth of the city library. There he told her he had some things to take care of and would return soon.

Something stabbed at his chest at the change in Yusra’s face. Gone that bright-eyed young woman he used to know. In her place, a woman whose heavy-lidded eyes were the eyes of someone ready to accept defeat.

On the way out, he shook the security man’s hand and thanked him. A foreign gentleman who helped them out whenever he could.

While Bennett did the rounds of the city centre bins, he wore blue rubber gloves to protect his hands. He lost count of the deposit-back bottles and cans he collected after he had a run-in with a grey bearded man who was likewise scavenging for bottles. He told the man that nobody owned the bins and that there was no ‘patch’ as the man suggested. But to avoid trouble, he left him to the bin in question.

Bennett’s first round of the bins brought him two black refuse sacks full of discarded bottles and cans. This yielded almost sixteen euro. He did another round, which brought eighteen euro and forty cent. Feeling lightheaded, he bought a bar of chocolate and ate a few squares. The rest he put away in his inside pocket for Yusra. Next he went to the city’s main thoroughfare and to the country’s largest supplier of books and magazines. In the art section on the first floor, he bought a drawing pad and a set of graphite pencils.

Bennett crossed back over the bridge that cut the city in two and made his way past his old alma mater, the country’s leading university, and on up through the pedestrian street which led to the Victorian park. There he found an empty bench and got to work with his pad and pencils. Although months had gone over since he last captured images on paper with pencils, his hand and eye worked as well as ever.

Pretty soon, a middle-aged American couple asked him if they could share his bench. As was the wont of their nationality, they struck up a conversation right away. They admired his work. Boldly, Bennett asked them if they’d be interested in him doing a double portrait of them. Wow, they said. They’d love that. And how much did he charge? He admitted that it had been a while since he had done portraiture, but he’d be happy to do one for free. Call it a mutual arrangement, he said. He’d get to practice and they’d, hopefully, get a memory from their trip to his country. When he finished, the couple insisted on paying him for his work.

Later that evening, Bennett and Yusra were on a train bound for the West. Yusra awoke from a disturbed sleep in his arms. She looked up at Bennett, her eyes clouded with tears.

“I’m slipping away,” she said. “I don’t know if I can hold on anymore.”

“I’ve got you, love,” he said. “Hang onto me. Don’t Let Go.”

*

About the author:

Steve Wade’s short story collection, In Fields of Butterfly Flames and Other Stories, was published by Bridgehouse Press in 2021. His award-winning short fiction has been broadcast on radio, widely published and anthologised, appearing in over 80 print publications. He has had stories shortlisted for the Francis McManus Short Story Competition and for the Hennessy Award, and was the winner of New Irish Writing in the Irish Independent for May 2025. Steve lives in Dublin.

Please see our Premier Writing page for details of how to submit you poetry, essays, or short fiction.

Leave a comment