Premier Writing aims to showcase the best poetry and short fiction by new and emerging writers across Ireland. This week’s short story is by Michael O’Connor from Dublin.

Short Story

Forgiveness

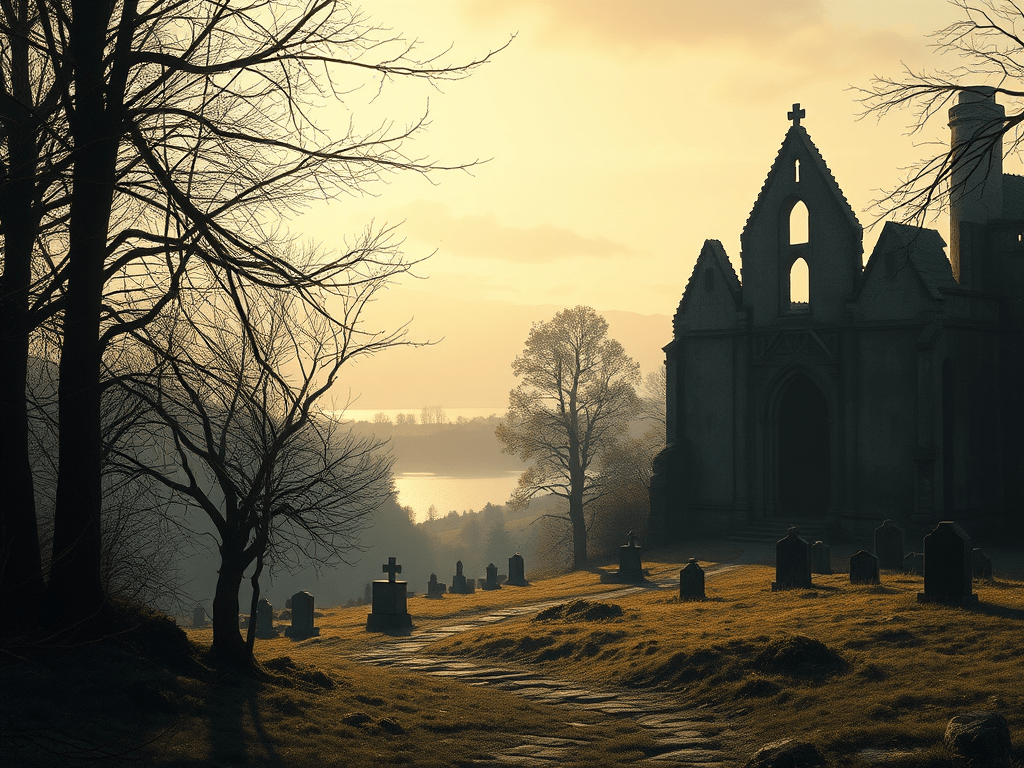

I LEFT EARLY, just after 6. I told no-one. Reversed quietly out of the drive and drove as quietly as I could up the hill until I had turned the corner. On the M50 I stopped holding my breath and speeded up. No-one around. Even the N3 was empty, but it was still early. Just before Cavan I took the Ballyshannon road and stayed on it till I got to Belturbet, then turned left for Ballyconnell, then left again for Milltown. It was a roundabout way, but I didn’t want to be seen. I’m not sure why. I wasn’t planning to do something I should be ashamed of. Nothing illegal. Nothing sinful. Nothing holyjoe. At Milltown, I passed the church, and turned left where the road bends to the right. At this point I usually go up the hill, but this time, I turned right and up the hill to Drumlane Abbey. Even here, on this narrow lane, I was more afraid of being seen than of meeting a car on a lane where there’s room for only one. If I had a head-on crash, I could live with that – or die with it – as long as nobody recognized me, or, worse, asked me what I was doing up here.

At the top of the hill, I parked the car and entered the old graveyard. The abbey was still, and the lake far below was still. Now, my car could be seen because it was the only one in the car park, just as I could be seen in the graveyard, but I didn’t care anymore. As soon as I reached your grave, I wished that I had brought a chair. Where would I sit? I stand when I haven’t much to say, and then I move on. I wanted to sit with you and, as the Quakers say, wait for the spirit to move me. I wanted to be with you, alone. Not only alone, but without anybody knowing I was there. Without anybody remarking on my being there, or making assumptions about why I was there. Without anybody assuming that I was mad, or grieving. Without anybody reporting my presence to anybody else.

It felt urgent that I should sit, not only because I would be more comfortable, but because when Ivisited you, you were always in bed, and I was always standing over you, because there was no chair in the room. And because I was standing over you, I felt obliged to talk. And when you didn’t respond, I talked more and more. I talk too much, anyway.

So, I wanted to sit. If I went to the car to get a camping stool, someone might come up at that pointand see me, and they would surely report to their neighbours. I took a chance on that. I walked slowly up to the car, opened the boot, took out the fold-up chair, closed the boot and returned to the grave. I didn’t hurry. It was nobody’s business why I was up here, and I wasn’t going to apologise. I set the seat down on the path beside the grave and sat. So. What now? It surprised me a little that I wasn’t in a hurry. I was with you. We were together. I was with you like those times when you’d be in the bed, wide awake, but not talking, and I’d be standing there like a gom trying to think of things to say, and probably pissing you off mightily. Who does he think he is? I imagined you saying to yourself. Does he think he’s doing me a favour travelling from Dublin? Now was different.

At the grave, I didn’t have to say anything. It was good to be sitting and silent. And even though I felt like saying sorry for all the times I had tried to make conversation when it was obvious that you didn’t want it, I didn’t say it. I didn’t have to say it. I felt it, and in the silence of the morning graveyard, I felt your forgiveness. I said an Our Father, and a Hail Mary and a Glory Be. I said them aloud and the purity of the words sounded right. They were a gift to myself and a gift for you.

And then I picked up the chair, put it back in the car, drove down the lane to Milltown, out as far as the Ballyconnell Road, turned right, right again at the roundabout that goes in to Belturbet, and straight back to Dublin. I told nobody.

*

About the author:

Michael O’Connor is a retired teacher. He has written novels, plays, short stories and poems, and has had poems published in the Irish Times, The Stony Thursday Book, and The Caterpillar. He has also read poems and prose on RTE’s Sunday Miscellany. He lives in Ballybrack, Co. Dublin.

Please see our Premier Writing page for details of how to submit your poetry and short fiction.

Leave a comment